So already, I’ve been thinking about the familiar sentence “And they lived happily ever after”* that often ends fairy tales and romances—and that I suspect many of us grew up hoping would one day apply to us.

Why now? The other day, I tuned in to the final third of a Hallmark “Christmas in July” movie called “Crown for Christmas.” Immediately I knew that Allie, Princess Theodora’s adored temporary governess, would marry her young charge’s father, King Maximillian of Winshire, much to the disappointment of Lady Celia. My early-life immersions in Cinderella and The Sound of Music had well prepared me to predict accurately that Allie and Max, despite their short acquaintance, were meant for each other, would wed, and then would live happily ever after.

Had “And they lived happily ever after” at all changed in meaning and application over time? I was already thinking about this as I walked through the public park near my home early this morning: John and Abigail Adams, I believe, had lived happily ever after, but, as the placement of their statues suggests, often across long distances during a time when people and letters traveled slowly.

I have to think that their shared commitment to their family and to something bigger than their family—namely, the shaping of a new nation—was part of their “happily ever after.” I think the same thing about Pierre and Marie Curie who loved each other, their daughters, and their scientific research.

Curious about the evolution of the use and meaning of that familiar definitive statement, I did two Google searches, one for explanations and one for images.

In terms of its meaning and range, the AI Overview at the top of my search page confirmed that the sentence still generally describes romantic relationships. But the overview was also more nuanced than I had expected:

The definition** didn’t promise a total absence of unhappiness; it did promise “free[dom] from significant hardship and sorrow”—though it steered clear of qualifying “significant.” It also referred to “a perfect, or near perfect, existence”—and we all know that even near-perfect sets the bar very high. But concepts of “perfect” and “near-perfect” are extremely subjective. In a recent heartbreaking Call the Midwife episode, a couple gave up their infant daughter for adoption because she wasn’t medically perfect. In contrast, the Japanese art of Kintsugi ascribes greater value to beautifully repaired broken objects than to the unbroken, “perfect” originals.

In a brief detour to Quora, I learned that “The first recorded use of 'happily ever after' occurs in a translation of a story by Giovanni Boccaccio's in his Il Decamerone, (The Decameron) published in 1702.”*** And that reminded me that “happily ever after” is hardly an American idea—fairy tales come from numerous cultures, continents, and countries, and long preceded the existence of John and Abigail Adams.

But American notions of happiness—we are, after all, the country that still promises “the pursuit of happiness” (and long may we do so, and get better at it)—may differ from those common in other countries. It’s worth noting that the sentence we’re talking about does not say “And they lived happily enough ever after,” which might better reflect some other cultures’ acceptances of suffering as the quintessential human experience. In contrast, for Americans, happiness is the aspiration and expectation, almost the entitlement.**** For many, “happy enough" doesn’t cut it, though it’s the most that most fortunate people get.

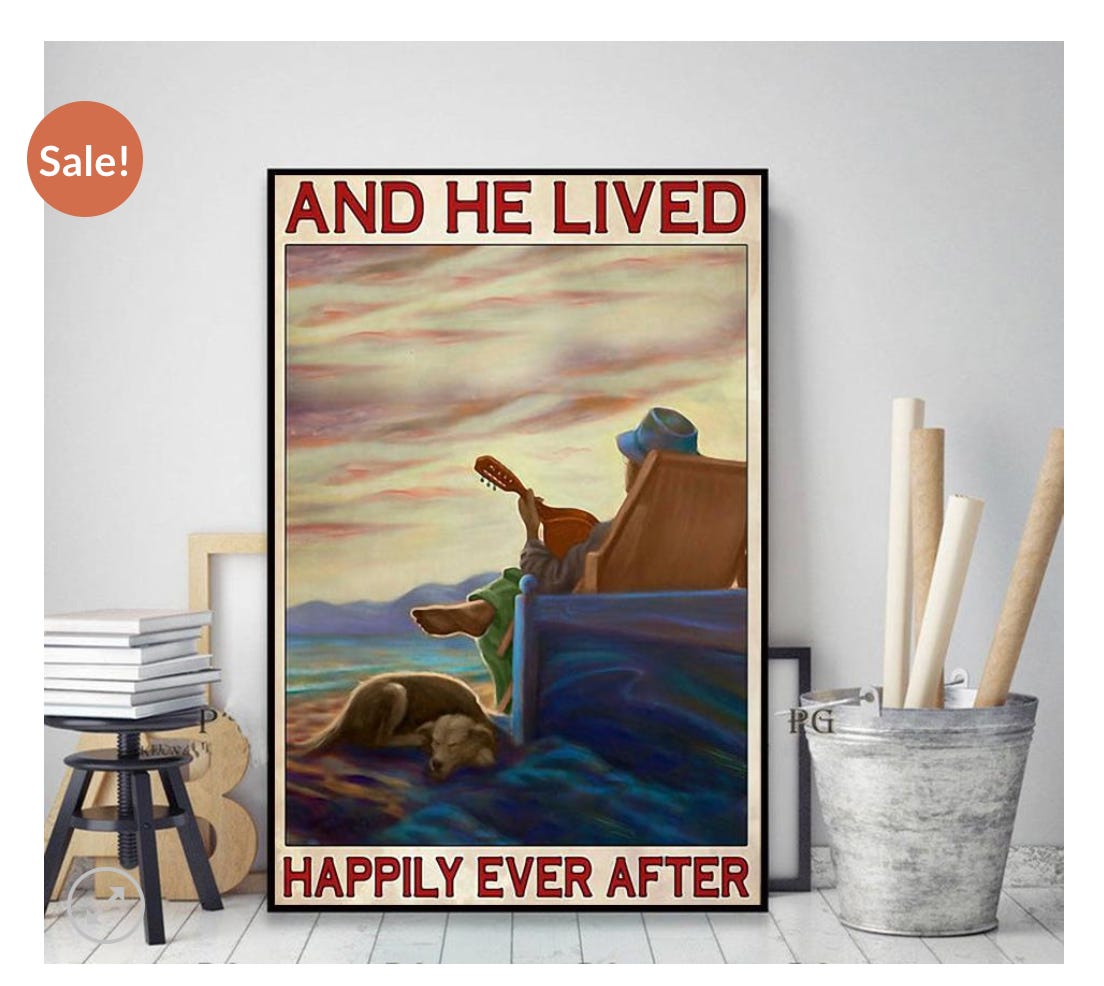

Moments later, my “and they lived happily ever after” image search on Google answered my question about the possible identities of the sentence’s “they.”

As confirmed by the items pictured above, “they” can refer to a woman who shares her life with man’s best friend, but not man. (Okay, we’ll leave that “man’s best friend” language alone for just now.) It also confirms that the pronoun “they” can become “she”—or remain “they” to refer gender-neutrally to an individual.

Thus, “happily ever after” is no longer assigned exclusively to two people who love each other in the context of an enduring and even formalized relationship. Sometimes it reflects expected and unexpected solitary satisfactions. Sometimes it reflects thoughtful or even unchosen trade-offs embraced over time. Sometimes it reflects new or amended dreams. Sometimes it reflects old dreams revived or past events newly interpreted or understood. Sometimes it reflects challenges accepted and met, sometimes against great odds. Sometimes it reflects having meaningful work, even if that work is sometimes relentlessly hard and discouraging. Sometimes it reflects crazy, unexpected good luck. Sometimes it reflects memories of places and people we can’t recall without needing to reach for the phone. Sometimes, it reflects finding out that we can do something we always wanted to do but didn’t think we could do. Sometimes it reflects realizing we’re happy though others think we shouldn’t be—this last statement brings to mind J.D. Vance’s famous “childless cat ladies who are miserable at their own lives” statement and the backlash it ignited.*****

All of the above said, “happily ever after” is still most often used in connection to enduring romantic relationships. As adolescence ends, many feel the pressure to find “the right one” to marry and live with happily ever after, which makes a great deal of biological sense if they want to have children. Some find the right ones in their twenties, and others find the wrong ones and have to start searching again. Yet others find “the right one” much later or not at all. And some don’t even try to find the right one. Unknowingly, the many now leading uncoupled happy lives helped challenge the idea that “happily ever after” belonged only to the coupled or married.

Is a committed, enduring, genuinely affectionate long relationship enough for “happily ever after”? My mother, born in 1928 and married to the man she met when she was eighteen, would have told you yes, especially because she was a mother, and even though she had some bouts with anxiety and depression. But there was so much about her life that she loved, and as she and my father grew old together, they continued to cherish—perhaps above all else—the time they spent together.

As for me, “happily ever after” is a far more multifaceted thing, even though I’m married happily enough. But I was late to the wedding party—didn’t tie the knot until I was 47. So I always knew that that there was a whole world out there beyond the two of us, filled with rewarding, complicating things, many worth loving.

Recently I finished reading Elizabeth Strout’s Lucy by the Sea, about the year the recently widowed Lucy Barton lived with her ex-husband in Maine during the COVID pandemic. Not long before that, I finished reading Dolen Perkins-Valdez’s Happy Land, which featured a story within a story that also included several interrupted and then resumed love relationships. Love doesn’t always color inside the lines, and “happily ever after” can stretch and surround in some unexpected ways. In all of its forms, it’s what I wish for us all—except, maybe, for J.D. Vance and some of his associates.

P.S. If you enjoyed reading this, please consider subscribing to So Already by Joan Soble for free. Substack periodically may ask you to pay or pledge to subscribe, but I will not. Thank you for considering.

* Screen shot of photo included in the following post: Pasricha, N. (2010, November 18). #371 Seeing old people holding hands. 1000 Awesome Things, WordPress. https://1000awesomethings.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/old-people-holding-hands2.jpg

** Composite of 2 screen shots, one of the AI definition of the statement and the other of a greeting card found at the following address: https://upyourarsenal.com/products/b084 —image

*** John Welch’s answer at https://www.quora.com/When-was-the-phrase-Happily-Ever-After-first-used-and-how-did-it-become-synonymous-with-a-fairy-tale-ending

**** Yes, I am suggesting that Americans as a group are not as spiritual, ethical, and moral as I believe might positively affect to the country’s collective happiness. If it’s one thing these last years have taught me, it’s that certain varieties of fervent religious affiliation endanger the lives and freedoms of those beyond the religious folds identified by their affiliates. Politicized religious affiliations too often lead to the abandonment of central religious morals and values for the sake of political influence and power.

***** A great article from NPR about the history of the cat-related disparagement of childless women: https://www.npr.org/2024/07/29/nx-s1-5055616/jd-vance-childless-cat-lady-history

Thanks again Joan for another thought provoking post. I have recently been considering what is it that I would even want from a relationship with another person (if I were the sort to be in search of a life partner) and in my thoughts I tell myself it would be okay if it were okay simply to be open about the care one wants to provide for another. But then I am unsure that it is okay to sincerely care. By "care" I mean to be invested in the happiness or well-being of another in a way that puts forth effort. And that brings me to your little question about Why is the poster with the man in it on sale, and not the one with the woman. Well, please forgive my reach but it is not a very popular idea in this country that a man should be happy. (At least not that a dog or a beach or a guitar should be the cause of such a feeling.) Sometimes it feels like he cannot even smile in public spaces or express emotion beyond immediate desire. Not to discount all the men and other individuals in this world who seem to do just fine caring about all manner of happiness from their kids to their community. But I suppose there's only so much one can glean from one image on a search result. And I don't imagine that poster rushing off the shelf from any warehouse at any price.

-Berhan

Thank you for this blog, Joan! Lots to think about. One of the things that struck me about your blog is the importance of context and how the surrounding culture and values have forced changes in interpretations of what “living happily ever after” means. Coincidentally, I have been working on a long put-off quilt centered around fairy tales; not the amended Disney versions of the stories but the originals – both of which I grew up with. You sent me back to my copy of Bruno Bettleheim’s book, The Uses of Enchantment. He contends that fairy tales helped children to go from childhood to adulthood, learning lessons about “justice, fidelity, love, and courage” as well as conveying warnings about the fearsome consequences of the temptations of adulthood. It’s making me think more about Disney’s versions, and the original story-tellers’ versions: What are they conveying? How do they shape the thinking of their audiences? What do the stories tell us about who we were then and now? Thank you for stretching my thinking….it will end up in my quilt somewhere.